Up earlier this morning to catch the high slack tide leaving the lagoon of Fulaga to head to the next island of Ogea, only a 10-mile trip today, motoring on mellow seas with little wind. The pass into Ogea is wide and straight forward and we meandered to an anchorage off the uninhabited Ogea Driki.

Ogea is a small island in Fiji’s Lau Group, made up of two parts: Ogea Levu (Big Ogea) and Ogea Driki (Little Ogea). It’s primarily a raised coral limestone island with flat terrain, surrounded by vibrant coral reefs and mangroves, creating rich habitats for marine and bird life. Home to a close-knit community of around 100 indigenous Fijians, Ogea is known for its traditional lifestyle based on fishing, farming, and strong cultural customs. The island is also an important conservation area, sheltering the rare Ogea monarch, an endangered bird species found only in this region.

Our first anchorage site was in shallow amazingly clear waters, where we snorkeled bommies of vibrant fish among healthy coral, and hung out on the beach.

At low tide, water flowed down a shelf of high reef into the waters below, creating a long horizontal waterfall.

Father’s Day started with crepes made by the kids, followed with snorkeling bommies…tiny treasures from clown fish in their anemones to lavender corals. On the way back from a paddleboard and walk with Cora, I peered down into the shallow ocean to see an empty nautilus shell underwater. I jumped in for this gift of the sea; what a treasure!

The nautilus is a deep-sea cephalopod known for its distinctive coiled shell, which it uses for buoyancy by regulating gas and fluid within its chambers. Often called a “living fossil,” the nautilus has remained virtually unchanged for over 500 million years, making it one of the oldest surviving marine species on Earth. Finding a nautilus shell is amazing because it’s an incredibly rare natural treasure—these deep-sea creatures live at great depths and rarely wash ashore intact. Their perfectly proportioned spiral shell, following the golden ratio (approximately 1.618, that appears when a line is divided into two parts so that the whole length divided by the longer part is equal to the longer part divided by the shorter part) – a stunning symbol of mathematical beauty and ocean mystery.

The beautiful beach was lined with plastic bottles at the high tide line, sadly what we see in many remote beach locales. We had a good discussion about what to do with the piles of plastic we find on beaches. Leaving it seems the worst option, as it will end up likely back in the ocean and/or ingested by wildlife. Bagging it up and returning it to a dump if there are ways to deal with it is optimal. We did some further research into what would happen if we bagged it up and brought it back to the town of Savusuva: Savusavu’s plastics follow a “collect → coastal dump → leak into the sea” pathway, with only token amounts reused or shipped away for recycling. Until a lined inland landfill, a compactor/baler, or a regular barge link to the main‑island recycling plants is funded, that situation is unlikely to change. After even more digging: Savusavu’s main landfill (or “dump”) is located about 3 kilometres northeast of town, on low-lying coastal land. It’s right near the shoreline, without any impermeable lining or containment—meaning during heavy rain or high tides, lighter plastics and other waste are regularly washed back toward Savusavu Bay. Hmmm, so not great to bring beach plastics back to Savusavu (or even our plastic garbage onboard). Another option is to dig a pit above high tide line and bury it.

We decided to have a “controlled micro-burn of a small quantity,” where we built a fire and burned the plastic that was on that section of the beach. The positives are the immediate removal from the environment and preventing it from blowing back into the ocean or being eaten by wildlife. Negatives are that this method releases toxic chemicals (like dioxins, furans, and heavy metals) into the air. We ensured that it was completely burned up. And now what do we do with our plastic garbage on the boat…I’m feeling like bringing it back to a garbage can in Savusavu is a bad solution, as much of it might end up in the ocean. I’m currently reading about Ecobricks, plastic bottles packed tightly with smaller plastic bits and wrappers, used for building in some countries like Indonesia as a partial solution for all the plastic waste. So…what do you think is the best way to deal with plastic waste we find on the beach in remote Fiji?

Moving to a different anchorage off Ogea Levu, we walked 45 minutes through the jungle to the village.

As we walked through the village, a man waved us over. We took off our shoes and sat down with him and his wife, visiting for a while. I soon asked where the chief was, as we had kava for him for sevusevu. He and his wife laughed heartily; he was the chief! His father, who I had been looking for, had grown too old and passed on the responsibilities to his son. They were very inviting, bringing us coconuts themselves to drink, laughing with us when Chris’ coconut sprayed him in the face and as we tried to learn Fijian words. He performed the sevusevu, Cora later told us that she had a large beetle crawl up her sula that she had to subdue…I don’t know how she didn’t yell or jump up! I think any of the rest of us would have! The reading glasses we brought were a hit, the chief’s wife immediately trying them out and reading her book more clearly.

The village kids ran along with us, holding our hands and jumping along before their teacher cajoled them to their dance practice. The population is down to 76 people per the chief. We noted the elevated cement pathways and raised up houses, the ocean flooding their village more and more.

The water flooding Ogea comes from a combination of rising sea levels due to global warming and saltwater seeping up from the ground through the island’s porous coral base. During high tides and king tides, ocean water overflows onto land and mixes with rainwater that can’t drain properly. Heavy rainfall worsens the issue by pooling on the flat terrain, especially when drainage is poor. Additionally, strong ocean swells and storm surges periodically push seawater deep into the village. To manage flooding, the community has built elevated cement walkways and drainage culverts to keep paths usable and redirect water flow. Local youth, with limited resources, are working to reclaim flooded areas using manual tools like shovels and wheelbarrows. While some government assistance has helped temporarily, more permanent infrastructure and long-term solutions like seawalls or relocation may be needed. That night, we watched a documentary called “There Once Was an Island” about a Papua New Guinea island being claimed by the rising sea.

Chris and I went for a walk amongst the limestone mushroom formations at low tide before moving to the next Ogea anchorage.

On our way, Calder caught a Green Jobfish (in the Snapper family) before we tucked into our turquoise anchorage surrounded by limestone formations.

After a jungle walk to another beach, we enjoyed “happy hour” with the other two boat families here. We were excited when a local stopped by in panga, traded fuel for bananas, and bought breadfruit and baby bok choy. We laughed about cruisers liking breadfruit for chips – fish and chips, he joked. He confirmed that the jobfish was an excellent fish to eat and Ogea is free of ciguatera toxin.

Woke up to scattered showers and a full rainbow. Evening potluck on Terikah with boat families, fresh veg and jobfish to share.

We decided to sit out the winds in Ogea, which turned out to be a bit rolly at high tide (when water and waves pour over the reefs), but otherwise mellow time of boat life.

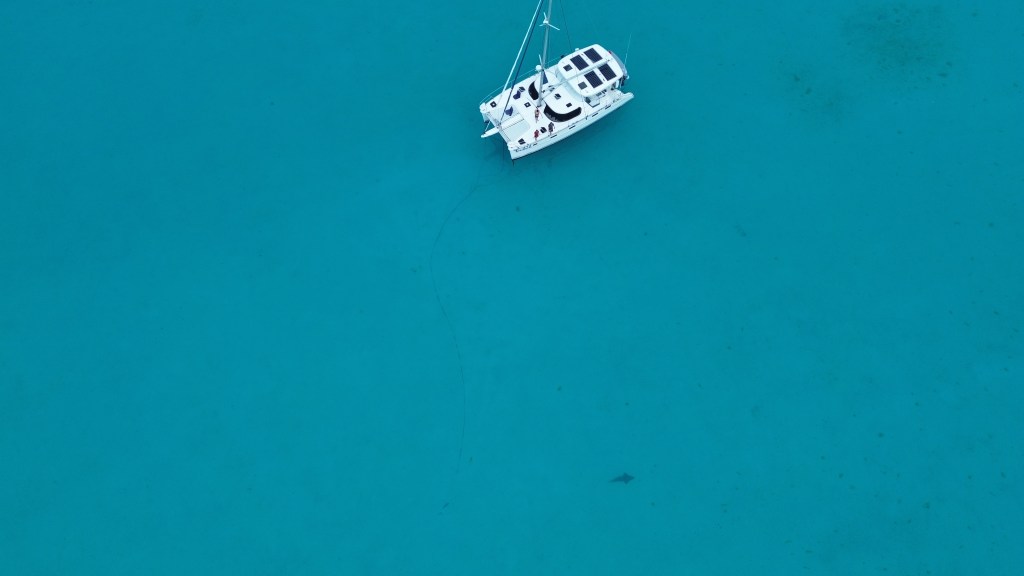

We have very little fresh produce left, a few cans of vegetables, and I’ve needed to be creative with some winners being “Carrot Tuna Curry” and “Deer steak with Spicey Peanut Sauce.” We’re back on daily vitamins to fill in the gaps! I’ve been making yogurt, loaves of bread, granola, buns, Naan, and learned to turn breadfruit into amazing tasting “fries.” Our final morning here was exquisitely calm, able to see the ocean floor all around us, as well as our full chain leading to the anchor and a shovelnose guitar fish (a type of ray). Off to more Lau islands exploration.

3 responses to “Ogea: Snorkeling Delights, a Village on the Edge, and a Gift from the Sea”

I hope you connect with Krister, Amanda and their 2 kids from Talkeetna. I don’t remember their boat’s name but I gave them your info.

So happy your are spreading good energy around the world.

LikeLike

I’m moved to tears when I see you folks interacting with the Fijians. We had such a warm and genuinely welcoming experience in a remote village like the ones you’re visiting. It was just 3 weeks after the 9/11 tragedy, and while the village was concerned about constructing a school building, everyone was so very concerned for us, and how we were feeling after the tragic event. People wanted to know if we knew anyone lost or were impacted personally. Such profound kindness! The most beautiful people.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the most beautiful people.

LikeLike